Jay Fisher - Fine Custom Knives

New to the website? Start Here

"Kotori"

Welcome to my FAQ page. When I first built the website back in the mid-1990s, there were not many frequently asked questions about my custom and handmade fine knives, so the FAQ page was simple, small, and quick to read. As inquiries and web site traffic grew, I realized that many of the same questions appeared repeatedly. I used to answer each of these individually, until I found myself spending several hours each day giving the same replies over and over. So I added the most commonly asked questions to this page, with what I hope will be clear and definitive answers, so that interested parties and clients can access them quickly, have them continually available, and maybe even have a chuckle or two.

The topics and answers here only apply to me and my works; other knife makers and artists will obviously conduct their business and tradecraft differently. Please remember that the information presented here is my own opinion, presented after having made knives for nearly 40 years, and professionally as a full time knife maker since 1988. Thanks for being here, without you, the reader, this website is not possible!

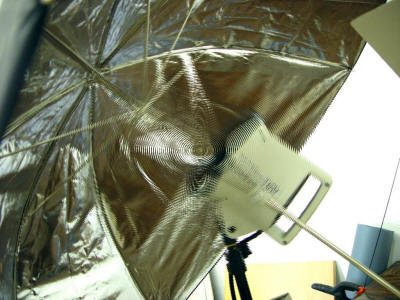

Throughout this page, you'll see this style of highlighted box. To break up the text, I've inserted some interesting photographs of and around the studio with some related comments and offer a little insight into my work making knives.

I've added comments on the treatment of the photos that I think you'll find interesting. All of the photos are thumb nailed, so please click on them to see a fully sized image. I hope you enjoy them.

Jay: I don't expect an answer to this email. I just wanted to tell you that, as a new maker, your site is extremely informative and just totally awesome!

Thanks,

Dick Absher

Woodturner, New Knife Maker, Retired USN(CWO4), and Retired Art Teacher

Bolsters are highly underrated in both the finished knife and in the construction and effort of building a knife. The bolster not only bolsters or strengthens the full tang knife blade, but also beds and anchors the handle scales, gives a thickened area for the hand to apply pressure to the knife handle, and offers an area for embellishment and artwork.

Here is a pan of 50 freshly cut bolsters in 304 high nickel, high chromium stainless steel, the same steel used to make stainless bolts and fasteners.

The photo was manipulated with a radial blur filter and the tonal curve modified in linear scale.

Short answer: It's about you.

Long answer: It's about your relationship with knives. Perhaps you've looked over some of the pages, and you see my knives, read what I've written, and hopefully smiled at my humor. You've undoubtedly learned something about knives and gained some insight through a professional knife maker's own eyes. Though I would love to say it's all about me, in reality, it's about you. Because you are reading this at this moment, you have more than a passing interest in knives, fine craft, and art. Otherwise, you would be on some other website. So when you peruse the pages, read and enjoy seeing what I see in the magnificent field of knives and art, please think about your own relationship with knives. It is not subjective, it is not objective, true art is interactive.

In very few other fields does interactivity with art come to such a basic act. A knife is a tool, and must perform the simplest, oldest, and most necessary function of interaction in humanity, which is to cut. Since the knife is man's oldest tool, it makes sense that we revel in its form, function, creation, and expression. At the core of our physical interaction with the world is this thing we call a knife. You have a direct, personal relationship to the knife and I invite you to share my own interactive expression in a refined, elegant, and durable modern tool. My hope is that you, too, will deepen your relationship with the knives in your life, and share that with others near you. Thanks for being here; it is about you, after all!

Jay,

I am the one who is in debt to you for letting me purchase the art works that you create.

I am so happy to be able to purchase classic art work knives without worrying about the quality and design.

Most importantly, I am dealing with someone who is old school whose word is his bond. In the world

I deal with every day, someone is always trying to scheme and scam you out of something. It is like a

breath of fresh air dealing with you.

--P.

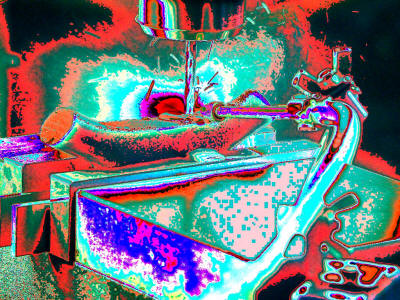

The belt grinder is the mainstay of the knife maker's shop and studio. The machine is simple, a belt and contact wheels, with abrasive belts that grind the wide variety of metals, ferrous and otherwise, manmade materials, hardwoods, horn, bone, and just about any material one can grind (except stone!). No matter how knives are made, the belt grinder is the tool that allows knife makers the freedom of shaping hardened, tough, and durable metals and materials.

This is a photo of me, hollow grinding a broadsword blade offhand... really!

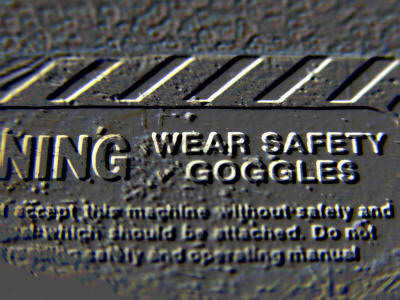

The photo was manipulated with a digital embossing filter.

Short Answer: I make knives. I also offer Professional Knife Consultation services.

Long Answer: I make and sell knives, by hand, from my own designs and by custom order. I also consult professionally, about knives. For more information about my Professional Knife Consultation services, click on the link.

This is a large website, and there are many ways to arrive here. So, at first glance, it can be confusing and overwhelming, even for me! There are a tremendous amount of knives on these pages (over 630 pages and 15,000 photos currently), accompanied by a massive amount of information, particularly for this field.

When someone sees the site for the first time, they may note the tremendous variety and scope of knives here. All of the knives you see on this site are made by me, one at a time, by hand. The only exceptions are the collaborative knives I've made, mainly with family members who have learned knifemaking from me in the past. Every knife you see on the site that has only my name on the blade (the Maker's Mark) is of my sole authorship, made completely by me, in my studio. Nearly every photograph is also my work, and every word that you read, aside from the testimonials, is my own creation. Simply put, I make and sell knives, photograph them, describe them, and offer what I have learned and know from nearly 40 years as a knife maker.

The knives I make and offer are of two types: Custom Orders and my own Creative Works (finished knives).

Don't worry about using the wrong word or phrase if you contact me about a knife project. I'm expected to know these terms, not you; I fly the plane, you just tell me your origin and destination.

A process I offer in the studio is knife sculpture. One of the exciting aspects of this is actually a very old process, that of lost wax casting. I carve clay or wax models, either mold or create one-of-a-kind originals, and follow up with investing a mold and either gravity cast, vacuum cast, or centrifugally cast molten metals into the mold. My favorite is silicon bronze. This allows me to create entire sculptural works, fittings, stands, displays, or components for my original works of knife art.

This is a photo of the casting pour, molten bronze at 1975° F is being poured into molds that are 900° F.

The photo was manipulated with a bright molten bronze colored vignette, and a vertical wind filter.

There are many kinds of handmade knives and knifemakers who make them. Most are hobbyists and part-time knifemakers. A very few are full-time professional career knifemakers. This is what I am. You can learn more about knifemaking on this page.

When someone first encounters my website, they can be overwhelmed at the information, photography, and the sheer amount of knives. It's easy to see that the knives are beautiful, truly works of art. Is a work of art to be used, or is it to be collected as art and investment?

The confusion starts with the perspective that a knife cannot be both, and that's in error. Any beautiful tool can be appreciated not only for its appearance, but also for its function. To clarify that a bit, here's a response I gave to a person who asked, "Are these working knives or art pieces?"

To answer your question about knives for use, or works of art, the answer is yes and yes.

The most important aspect of making fine knives is that they exemplify their position, first, as tools. In doing so, my goal is to make the very best knives possible, with absolute premium materials and advanced, even extraordinary process and treatments. From steels to fittings, from handles to sheaths, stands, and accessories, the entire scope of work is based on working tools and function. Many of the knives I make go to specialized users: chefs, outfitters, military, rescue, and counterterrorism professionals. The knife is first and foremost, a tool.

As the quality and execution of knife creation advances, the materials, finish, and embellishment also advance. For example, a mirror finish on a knife blade is not just for show; the smooth and polished finish dramatically improves corrosion resistance and with the proper heat treatment, repassivation of the steel increases corrosion resistance even more. This is the evolution of construction of the tool.

So, also, is the advancement of the handle material. When people see gemstone (mineral) handles for the first time, they may believe that they are just for aesthetics, and indeed, they are the most beautiful handle materials available. More than that, they are incredibly durable, eternal materials. Unlike woods, horn, bone, and antler, they do not absorb moisture or dry out, they do not shrink and expand, and unlike plastics, they do not scratch and dent and show wear. When you think of the longest lasting materials ever made by man, you realize that they are stone age tools and implements. Because stone is so difficult to work with due to its hardness and refractory nature, it’s rarely used but only on the finest knives.

Since the knife is man’s oldest tool, it is to be expected that it is refined to an extraordinary degree. This encompasses design, embellishment, and the accoutrements commensurate with the knife; it is all the purview of the knifemaker. Therefore, as the knifemaker advances, his work will necessarily be collected and be appreciated for its investment value.

I suppose that’s more of an answer than you expected, but this is why fine working tools can become instruments, and then investment art. They are both tools and art.

--Jay

My knives are used professionally, by military and counterterrorism professionals, by chefs and restaurateurs, by guides and outfitters. They are also collected for investment, purchased and kept for heirlooms, and used and admired daily. Every knife I make will outlast me, and the following generations of owners and patrons. It's a humbling honor to know the work of my hands and mind will be around and valued not only for its aesthetic appearance, but for its prime functionality.

They are tools: beautiful, timeless tools.

Short answer: Yes. If it has only my name on the blade, it is ALL my work.

Long answer: I make everything you see here, except (obviously) the knives in collaboration.

I start with a six foot long bar (billet) of annealed and spheroidized high grade tool steel. Tool Steels are a special classification of steels, made by special metallurgical processes, and must be hardened and tempered and treated with highly specialized equipment. I add to the process raw rock, horn, bone, ivory or wood. Rock in this case means gemstone, either solid masses or groups of minerals that form semi-precious and precious gemstone. The manmade materials I use for handles are the finest, most durable, and most dependable created in our modern times. The horn, bone and ivory I may use is of the tougher variety, and may be stabilized, partially mineralized, or specially sealed to increase the durability. Woods I use are tough, durable, and may be exotic, rare, or domestic.

I design the knife from the ground up, and currently have over 500 patterns. I profile, drill, mill, shape, grind, heat treat, finish grind, and polish the blades, I profile, shape, finish, polish, and attach bolsters and guards. I saw and slab gemstone, cut, grind, drill, shape, sand, polish, and attach gem handles as well as manmade materials, hardwoods, and horn, bone, and ivory. I design, create, and execute all the hand engraving you see on this web site; I do all the machine engraving, I do all the high resolution etching, artwork, and design. I do all the chemical processes, including diffusion welding, etching, electroplating, electroforming, and several different types of professional hot bluing and antiquing. I heat treat in inert atmosphere controlled furnaces, do complete and sophisticated shallow and deep cryogenic processing of my knife blades. I perform the gas tungsten arc welding, the shielded metal arc welding, brazing, soldering, and multi-process welding. I sculpt wax and cast bronze, silver, brass, and nickel silver fittings, components or display stand elements. I make every part of the sheaths, the stands and the cases; I do all the carving, hand-dying, inlaying, and stitching. I make every component of my knife stands and cases, from design to sculpting, carving, carpentry, joinery, embellishment, and finishing. No other hands are involved in my knives! If it has my singular maker's mark on the blade, it is all my own work.

I also design, build, maintain, and repair specialized shop equipment, electric motors, machinery and controls, lighting, jigs, tools, and devices. I experiment with new techniques, apply creative technology, and constantly strive to improve my skills and product. I do all the photography, write everything on this site (except the testimonials), build and maintain this huge site with over 15,000 pictures and 550 pages. It is the largest, most comprehensive website of any singular knifemaker in the world.

I also vacuum the shop floor of the metal swarf, muck out the rock saws, sweep up the wood dust, and wash the windows (once every several years). This is my full time job and has been since 1988.

Knife makers may benefit from being educated on drawing, studying perspective, negative space, and relationships of objects. It helps to have a background in photography, as that can offer insight to density and perspective.

The older I get, and the more I learn, the greater the amount of time I spend at the drawing table.

Benvenuto Cellini once said: "Though many have practiced the art without making drawings, those who made their drawings first did the best work."

A high contrast photo, warming the surroundings and washing out the subject. I start nearly every project on the drawing table, using references, tools, and a lot of erasers until I get what I want and what my clients desire!

Hi.

I just found your website yesterday. I was doing a search on desert ironwood, and I happened across the 'wood'

section of your site. After I finished with that I started looking around, and I must say that I am very impressed,

not just with your edged creations, but also with the site itself. I have never seen so much useful knife related

information on a single website before (and I use the word 'single' in the loosest possible sense, as it is huge).

It is a digital treasure trove of information for anybody that is interested in anything that has to do with knives,

and it is all available for free.

While I am not currently able to afford one of your creations (or to be more honest, I do not think I will be able to justify it to the wife), thoughts are spinning in my head already about how my dream knife would look. Amber handle scales in particular keep making an appearance. If I later feel that I can justify spending several thousand dollars on a knife (and I think I will, given time), I will definitely contact you again to discuss the possible project.

For now I just wanted to say thank you for everything that is available on the website, as all the information and inspiration is greatly appreciated. I spent about four hours reading and looking around yesterday, and I have done almost as much already today. I must say I appreciated the humor in the 'what I do and don't do' page in particular, as it made me smile several times.

I understand that you are a busy man, so I am not expecting you to respond to this e-mail, A response is not needed. I had something on my heart I wanted to say, and now I have done that. Perhaps we will talk together about a project sometime in the future.

Sincerely,

Truls Lindskog,

Norway

Short answer: As long as it takes.

Long answer: This is the most often asked question to knifemakers. I can make a simple, basic knife in about 16 hours. A basic knife described here has a satin finished blade, full non-tapered tang, no bolsters, hardwood handle, and untooled leather sheath. I rarely make this kind of knife any more, as most clients expect much finer and more elaborate work from an established maker.

Some pieces I've worked on for weeks; some take months; one in particular art piece cost me a year and a half. It depends on how much work goes into a piece. Design and engraving takes extra days, filework takes hours, grinding through 12 steps takes many hours. Handle finishing is done off hand; often the sheath work and stand are not even considered by the curious when they ask the question. In some tactical and counterterrorism rigs, the clients request multiple sheaths and many different mounts for a variety of wear options. When you make everything by hand, including setting up, repairing, building shop tools and jigs from scratch, knife making takes a tremendous amount of time. It is not a casual endeavor.

Sometimes the person who asked about the time is considering just how much I get paid by the hour. You can see the little calculator clicking away inside their skull, trying to figure my wages. They don't know about materials and supplies, abrasives and electricity. They don't know about shop overhead, machinery cost, material prices, and failure rates (yes, things break, wear out, and are used up).

Let me set this straight. I can make an inexpensive knife for about $12.00 an hour. Yep, that's not much considering the decades of practice I have. Also, making $12.00 an hour in a shop with maybe hundreds of thousands of dollars of equipment and supplies and 40 years of training and experience does not make sense. That's why I make knives that start at about $1000.00. This way, I can make maybe $13.00 to $15.00 an hour! You've got to love it; your not making knives to get rich.

If your idea is to get rich making knives, you would be better served to start your own knife factory, make a cheap product that competes with imports, or better yet, have the work farmed out overseas and assembled here in America (like so many factories now do), and claim that it's Made In America. But then, you would be a manufacturing interest and not an artist. People who are creative artists for a living are driven by a passion for their trade, not a passion for a dollar.

A young man has to be told repeatedly to wear his safety glasses in the shop or on the job site. As he gets older, his corneas stiffen, and he has to wear magnifiers just to see close up.

I've found that as I grow older, I prefer strong magnification and the security of knowing there is something solid between me and all the dangerous swarf, sparks, chemicals, dust, and exposure.

Binocular magnification is a must; from simple 1.75 power glasses to a 30 power binocular microscope; a wide range is necessary for a variety of jobs.

Nice focus control in macro mode on this pic.

Short answer: Get in line.

Long answer: Because I make extremely fine and sophisticated knives, the work takes a lot of time. My clients expect the very best knives for their money, and I guarantee their satisfaction. Consequently, making knives this way takes a lot of time, more than most people realize. Considering the investment value and quality of fine custom knives, this is how it should be, and my clients are willing to wait for fine hand craftsmanship, not hurried, with attention to detail.

A while back, a writer for a magazine insisted that he watch me make a knife from start to finish, taking notes, photos, and documenting the experience. I warned him that it may be boring watching someone work at a machine for hours; he insisted he was up for the experience. After two hours watching me stand at the grinder, he left. He simply had no idea.

A long time ago, I realized that if I hurry, I'll make a mistake, and the whole project gets pushed back or worse, has to be started over (eek!). In this world of instant gratification, I do offer a solution for those who are unwilling to patiently wait for their hand-crafted knife, sword, or project. Go to the finished knives for sale pages here and here. There you may find fine work that is ready to be shipped immediately, but new inventory knives posted there do not typically last very long.

For those of you who've ordered custom work, the best thing you can do to help me out is to be patient, and know that it will be worth the wait. If I've given you a time frame for your project, please remember that it is just an estimate, based on the current work load (which changes almost daily).

Delivery times are a hot topic, so I've dedicated a page to the subject. Click here.

Hey Jay,

I have just spent about 4 hours on your site (just kept opening tabs with more useful information), and

I'm going to have to keep this brief because I'm aware of just how many emails you must still get.

Man, what a fantastic resource your site is, how well written, how honest, how informative. Being raised

in Sydney, Australia, I was raised to view weapons as tools used only by military / law enforcement, and

a sign of insecurity or aggression if carried by a civilian (it's very different over here, I've never

seen a knife displayed in a home, let alone carried on a person, save maybe a

Swiss army knife). Becoming

older however, I've revisited previous assumptions, and it's just fantastic to read about your craft,

and not just your knife making, your philosophy on things, it's bringing me around.

Being an avid hiker, I'm all but sure one day I'll be emailing you with a design for my own Jay-forged knife. The only thing is, your

website has created just as many questions as it solved. I've realized it's going to take me a year to even work

out and express to you what I want in a knife. Although the solution of course is to have you make me a dozen

knives, one for each task, since I probably still need to eat, I plan to dream up the perfect knife for the average

tasks I will encounter from now till forever.

Short version: Your website is inspirational and awesome, keep doing your thing! Currently finding more work so I

can be a proper Jay customer some day soon.

Kind Regards,

James Bailey

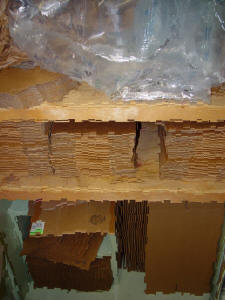

These days, the order rack stays pretty full; I'm thankful for that.

Sometimes guys start worrying about how their knife is progressing, and their order hasn't even made it to the rack, it's still in the file in the office.

The printed sheets help me keep everything straight; each project and knife has a specific designation.

I used a large rectangular pixilation in this photo to accentuate the repeating sheets of paper.

Short answer: Prices start at $1000.00 and go up from there.

Long answer: That $1000.00 knife is a skeletonized working knife with a simple sheath. This is rarely the type of knife clients want me to make, so prices average much higher. How much is the average? This is impossible to calculate because I make so many different kinds, styles, and types of knives and knife projects.

The cost of a project depends on five factors:

I use a strict pricing structure, based on 67 points of the individual knife construction. This way, I can calculate exactly what work goes into a knife and offer a fair price to everyone without guesswork. For more specific discussion and pricing details for my custom knives, swords, daggers, folding knives and artwork, here's a dedicated page.

For more information on these individual components of custom handmade knife construction with many examples, pictures and more in-depth details, here are some important links on this site:

Remember, there are many makers who won't even talk to you for less than $5K. I know of one guy who does the same looking knife over and over, and he doesn't even consider making a knife for less than $7000!

Someone once asked, "Why would anyone pay over a thousand dollars for a knife?"

The answer is simple: because they understand the value, and they can afford it.

The prices of my current works change from time to time. The utilities, supplies, and materials I use to make the knives go up constantly, as does the cost of keeping a piece current, maintaining it on this website, and the utilities of storage, shipping, and care costs as well as the costs of maintaining the knife shop equipment, storefront shop building, and this website.

In addition to my costs, as my work becomes more popular, the prices go up. Simply put, the more in demand a piece of artwork is, the more valuable it is. This also helps my existing clients, who have pieces that they expect to increase in value over the years. Their investment value grows, and so does the value of my older works, whether in the hands of clients or waiting on the website for purchase. Incidentally, my pricing structure for new knives grows too, as does the basis and the cost of the 67 points I use to determine price.

Though I use detailed guidelines for pricing quotes, I stay away from itemizing each feature to justify a price. For a deeper discussion on price justification, please click here to jump to the topic on my "Business of Knifemaking" page.

I detail payment types on the pages listed below. Most of my clients pay by personal check or cashier's check sent in the mail (USPS), through UPS, or FedEx, or they pay by direct bank transfer.

Beginning in March of 2017, I've stopped taking credit cards for payments. The reason for this is because for over two years, not one client had used a credit card to pay for their purchase. It makes no sense for me to pay for a merchant account when none of my clients are using it. Clearly, direct wire transfer and checks are my client's preferred way of paying for their purchase, and they may well be using a credit card online through their bank to complete a wire transfer. Exchange of money for services and products is evolving, and I believe that in the future, wire transfer will be the main way that money and payments are made.

For more information:

Files are one of man's simplest tools, yet are capable of an unbelievable amount of cuts, forms, and shapes. Though there are only a handful of file shapes, there are numerous sizes, cuts, and wear conditions. A worn file may still be a useful file, creating a softer cut with a smoother edged line.

Cutting can benefit from liquid solutions and wax lubricants, easing clogging and reducing friction and heat. A simple file cleaner is denatured alcohol.

File handles are very important. Most are too small for comfortable use.

The photo is manipulated with contrast tracing, embossing, and light solarization.

Short answer: Yes I can, but why?

Long answer: Sometimes a client receives a quote from me and realizes he's chosen features, materials, finishes, and embellishments that are out of his price range. With custom knives, the inclination is to go all-out, to get the features and materials you want, often because it's a dream knife, sometimes even a once-in-a-lifetime investment. The client wants his money to go as far as possible, and also wants a very fine knife, one that will appreciate in value over the years. A knife made to these high quality standards will often become an heirloom piece, graciously handed down through generations. If only he could buy the knife ... for a lot less.

If a client needs a lower price, the conversation between client and maker might erode to a line by line evaluation of each feature, cutting away what is refined and valuable, and leaving out features in order to fit the knife within the budget. The knife concept will ultimately suffer to become less than ideal, and less than the client (or maker) imagines. This is not a way to commission a fine handmade custom knife that will be worthy of investment, use, or collection.

From the knife maker's perspective, it doesn't make a lot of sense, with a high shop overhead, plenty of orders of fine pieces, and over three decades of hard experience making knives to then make budget knives. There are already a great deal of inexpensive knives in the world for sale: from makers, from factories, from dealers, and outlets for a modest price.

As the maker's clientele become more vigilant of the maker's trends and knife values and the maker creates a much better product in higher demand for higher prices, it is clear that the maker should serve his existing clients by only making the very best of knives. How might the collector of fine handmade knives feel if his favorite knife maker is now creating a cheap, quick product? This direction might indicate that the interest in the maker's work is waning in the marketplace, and this devalues existing collections.

How to say it clearly without causing offense? Here's an email response where I tried to do just that:

Thank you for considering my work. I’m afraid that I'm just not making

any low end knives currently; most of my clients are

requesting finer knives. Once we start whittling away the

features, materials, and finishes in the sake of economy,

the knife would be less of a knife overall and probably

wouldn’t do justice to your investment.

Thank you for your interest,

Jay

Only one thing can be said of clamps in the studio and workshop. You can never have enough.

These are small cantilever clamps used in my folding knife work, and hold strong and parallel.

In Great Britain, they call these "cramps." I'm sure our wives would raise an eyebrow...

This photo was taken on macro setting, with good depth of field for such a close shot with flash.

Short Answer: No, thanks; this is not a fruit market.

Long Answer: Occasionally, I get asked to consider a offer from a potential client that is lower than what the knife is listed for. Simply put, this is not something I do. There are several reasons that I don't do this, and you can apply this logic to other businesses, other knifemakers, and your own work and pay. When you do, I'm certain you'll see the integrity of fixed prices.

A client might think, "Why not ask? It can't hurt to ask, and maybe Jay will drop his prices."

No. But I will try not to be insulted.

Bargaining, bartering, dickering and haggling applies to petty items.

A fine handmade knife is not a petty item.

I've seen all sorts of reasons why these potential clients can't afford my work; some of them even ask for total donations! I've had people send unsolicited gifts, write long sad emails, and detail their painful circumstances while ignoring the fact that I have my own bills to pay so my family doesn't starve in the dark. This brings up the simple statement:

When a sale is made, it's simple logic:

The buyer understands the value, and he can afford it.

To the potential client who does not quite understand: The last thing I want to do is impose any financial burden on my clients. Every knife will sell, or I'll be happy to keep it. I'm not desperate; don't demean the conversation by haggling. I'm a professional; this is not a fruit market.

One more thing: How fair is it to all the other clients who do purchase my knives, often saving up for years to do so, in order to get the very best. That best may hang on their gear when they are in combat defending our country for freedom. How fair is it to let someone, anyone, pay less than they have? More about this on my Business of Knifemaking page.

Return to Topics

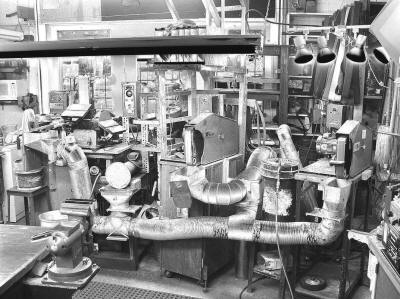

I always wondered what the grinder nest would look like if everything was made of chromium steel...

The grinder nest is an extremely important part of the studio, and you can tell a lot about the knifemaker by the grinders. Are they well made, safely equipped, tidy and well-lit?

A functioning studio must be constantly upgraded and this means all of the equipment, controls, dust collection, lighting, and even matting on the floor.

This photo was enhanced with "chrome" mask function, with contrast control.

I make tactical, working, rescue, combat, and counterterrorism knives. Since they are real tactical knives, not just "tactical" in appearance, they are actually made to be worn and used in the most serious of uses. Because of their real world application, it has been necessary over the years to include everything my clients request for them.

This starts with the toughest, most durable, and best made knife sheaths in the world today (and ever): my positively locking sheath, my hybrid tension-locking sheath, or my new tab-lock sheath. My experience has been that since the sheaths have to be worn, and since everyone is different and every mission or application is different, it's important to include all of the necessary straps, clamps, hardware, mounts, and equipment to wear each knife and sheath with every tactical knife.

It is rare that a tactical knife is only worn in one place; as the owner's gear is refined and regularly upgraded, the sheath must be able to mount to an evolving combat framework. Typically, a client who wears these knives will have multiple applications and missions, and because of the limitations of his other gear, he'll have to move the knife and sheath to different locations to accommodate. For example, the United States Marine in desert warfare currently has only about one place he can mount a tactical knife, and that is along his leg, below the waist, and above the knee. Of course, this may change depending on his particular gear, environment, or mission. I want my clients to have all their bases covered, and every option available.

From time to time, I receive requests for tactical knives that are "bare bones," that is just the knife and sheath, and no accessories. I rarely do this because of the reasons above, but taking it a step further, let's just examine what would happen if I did offer simple knife and sheath combinations, without all of the other hardware.

I've had the experience of doing this very thing; this is how I used to make and sell my tactical knives. When I did, the first thing that would happen would be the client contacting me and saying, "Gee, I really like the knife and sheath, but do you have a way to mount it lower on the belt?"

This is how and why I developed and include the BLX, UBLX, and EXBLX Belt Loop Extenders.

Then a client would ask, "Is there any way I can mount this horizontally along my belt line?"

From this, I developed the Horizontal Belt Loop Plates.

Then a client would ask, "Is there a way I can fix the sheath to my PALS on MOLLE, or vest webbing?"

I developed the Horizontal and Vertical Clamping Straps.

Another client would ask, "Can you make something to mount the knife over my sternum? It's the only place I can wear the knife. And by the way, it has to be handle-down."

I created the Sternum Harness and the Sternum Harness Plus.

A client submitted, "I do a lot of work where I might be in the field after dark, and sometimes, even in the daytime, I need a small light for examination or emergencies, or just finding my way."

I created the LIMA, with the Maglite® Solitaire, then the Solitaire LED, and then the ThruNite® Ti3 LIMA.

Then clients asked, "The little light is great, but can you actually give us a main (or key) flashlight. We need one that can be our main lamp, with super-bright illumination for nighttime operations. Oh, and we need it to be able to be aimed in a fixed position, in any direction from the sheath. Then, we need to be able to remove it, replace it, and depend on the holder to never rust, corrode, or bend."

I created the HULA with Maglite® XL100, then XL200, then MagTac®, and then Fenix® E35 and Fenix® RC11, and Streamlight® Sidewinders, and the Powertac models. My counterterrorism clients claim that "Two lights are only one light, and one light is no light." This is a logical, serious, and practical observation, since lamps can fail, batteries can die, and components in flashlights, no matter how tough, can stop working. A simple failure of a light can leave the owner crippled in the darkness, so most CT kits have both the LIMA and the HULA.

Some of the accessories were needs that I noticed, like the simple need for a touch-up sharpener, so the pocket on the UBLX was added with a DMT Dia-Fold® sharpener. Another was the fire starter for outdoorsmen, less often requested. I had knives with lanyard holes, but no lanyards; two types were added. I've added real diamond sharpening pads with essential pad-bags to carry, store, and use them. When I noticed that some of the drawstring bags the knife kits were stored in were literally worn out, I looked for a durable duffle that could accommodate the entire kit. There were no duffles of any strength or durability, so I saw the necessity to create my own, with 1000 denier, polyester-coated, water resistant Cordura® ballistic nylon and heavy 2" wide straps and large, durable zippers. I even added Velcro® patch removable embroidered name tags so the client can tell one of his Jay Fisher knife kits from another!

Consequently, the kits grew, and continue to grow to this day. My logic is this: I simply want my client to have everything associated with his knife. It's part of my service commitment to my career field.

Let's just look at what happens if I don't include all these accessories in the kit. I can reveal this because it's happened before. The client buys just the knife and sheath. He then notices that the sheath is a fixed form, and has a definite and universal mounting hole arrangement for straps and hardware. Since no one else in the world makes this, he then contacts me because he wants a different mounting or wearing arrangement. It's just a few straps to create, and maybe I can match the color of the anodizing with the rest of his gear, but maybe not, since I anodize in batches. But in order to make his accessories, I would have to stop what I'm doing (while five years in backorders) to make the parts. More logically, he should take his place in the queue, and wait five years for his straps to mount his knife. What? And then later, he wants a UBLX, but it's custom made for the knife (they all are) and I have to have the knife shipped back to me, so I can get the sizing and arrangement correct for the custom fit, and maybe he has to wait five years for that-

You can see why this is impractical.

Another point is that sometimes, a potential client may think that if I just offer the simple knife and sheath combination, he'll get a big discount and get the knife for less money. And then, he can add those accessories as time goes on, to spread out his investment. That doesn't work either.

If a client is strapped to pay for the kit, he probably should not be buying the knife. Most other knifemakers won't say this, but the last thing I want to do is to impose any financial burden on my clients. I know what it is to live and work within a budget, and I also know what a tremendous amount of work it takes to make these knives; they are quite literally the finest, most complete tactical knife kits in the world. If you don't think so, I challenge you to find any that compare, anywhere. The fact that they are so difficult to make is why you don't see them anywhere else. This means that the incredible amount of labor means a higher price. As I've stated before, I'm not interested in making budget knives; I've only got one life and one career, and I want to make the very best knives (and kits) I can possibly create in that time.

They arrived today. I expect perfection and you delivered as always.

The kits were a surprise to me. I know this sounds stupid to you, but, I am so use to

a masterpiece and a sheath to be put on display. The embellishments, on the weapons, cause

one to look at them as art pieces and not weapons of war. The kits bring home the seriousness

of your works and the need for full kits. In the future I will get full kits.

I would guess the majority of patrons do not truly understand what you do. The trolls and detractors

miss the mark completely. Your creations mean the difference between life and death.

Yours Truly:

P.

Since nearly every single one of my knives is shipped to a destination, it's important to know that they will arrive in the condition they're sent, as soon as is reasonably possible, at a reasonable cost. Shipping is no place to cut costs in the modern internet based business of making fine custom knives, and with today's technology, packing, tracking, and care are paramount to the completion of an order.

A package from me doesn't only include a knife. It includes an engraved acrylic permanent description plate, a bio sheet, a care sheet, and a cover sheet. It includes the receipt, business card for your file, and any information or reference material you might need. I want the experience of opening this package to be the height of the entire knife ordering process; it should be!

I don't rest easy until I've heard from the client upon delivery. What they think about their new knife, knives, or artwork upon delivery is my most important feedback.

This photo of shipping boxes is manipulated by a puzzle filter and contrast adjustment.

Short answer: the best fine, modern, high quality, high alloy, high strength tool steels.

Long answer: I use about a dozen types of fine tool steels, and like most makers, I have my favorites. These steels are modern, high tech tool steels made to the highest quality and purity that the foundry can produce. Most of them can not be hand-forged, because of their high alloy content, high critical temperatures, and high purity process requirements. They must be treated in a clean, specific environment, with careful steps of stress relieving, annealing, heat treating, and tempering. Most are high alloy, hypereutectoid, and benefit from cryogenic processing that I do right here in my studio. My clients expect the best, and these steel types have a proven record in combat, rescue, professional use, kitchens, and in the counterterrorism field, and retain their investment value in collections. Here they are with some of their properties:

I also use other specialty steels, like stainless damascus and powder technology steels. Pattern welded damascus is decorative and beautiful, but no matter how well it's made, those layers constitute welds, potential places of stress in the billet. Although most of pattern welded damascus is entirely usable, I don't use it in high strength tactical models, when a client requests "shove it in a rock and stand on it" tough. The other specialty steels that I use are expensive, hard to work, and have definite applications, but each has specific characteristics and limitations. They are RWL-34, W1, A2, BG-42, 440V, CPM440V, CPMS30V, CPMS60V, M2, CPM154CM, CTS-XHP, and more.

Custom knife blades deserve their own page, and mine is one of the most popular and detailed in the world. Click here for my Blades Page.

Return to Topics

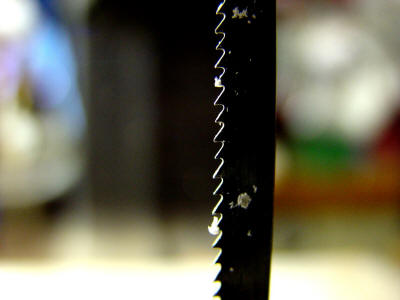

Profiled blades seem to multiply around the shop. When a maker is tired, or has just a few minutes before lunch, or just wants to do something mindless, he can usually cut out a blade. It's slow, boring work, as cuts are made with a slow moving high cobalt band saw blade.

People have asked why I don't use a plasma cutter. Because the edge will be burned, or at the very least, the alloy properties and distribution may be compromised, and I won't take that chance (particularly at the critical cutting edge).

A water jet may be nice to use, but I have too much of a variety of patterns to justify it and I don't farm anything out.

The letter designations are my tracking system.

Short answer: They're the best.

Long answer: Okay, I make a lot of gem handled knives. In fact, I make more gemstone handled knives than any other single maker in the world. That's rock, real stone, not the plastic stuff that is made to look like rock and then called "stabilized." That's one of my fortes. I have a complete professional lapidary shop nested in the knife making studio. Lapidary is the art and skill of cutting, carving, sculpting, and polishing of precious and semi-precious gems, rocks, and minerals. I can start with a two foot in diameter boulder and cut it down to a beautiful handle, nicely shaped and carved, brilliantly polished, and luscious to hold in the hand. Stone is cool, hard, and dense, and the balance is perfect.

I love gem for many reasons. It's impervious to all chemicals that a knife might be exposed to. It has a similar density and coefficient of thermal expansion as steel (steel is made of carbon, iron, chromium, magnesium, selenium, silicon, tungsten, molybdenum, phosphorus, and other elements, all found in rock) and gemstone won't expand and contract and eventually loosen on the knife like horn, bone, wood, plastic, and ivory do. It doesn't absorb moisture, or oils, or corrosives. It's hard, so it doesn't scratch. Some gemstone can only be cut by silicon carbide or diamond. Gemstone will outlast the knife blade in all cases. The very oldest tools, predating man as we know him, are stone.

Some people worry about toughness; if they drop it on concrete will it break? The knife blade TIP is the most likely thing to break on any knife so you shouldn't be worrying about the handle. But just to soothe your fears, the stones are usually protected in the critical areas by bolsters and the tang, or they are nearly as tough as the blade (particularly nephrite jades, flints, quartzes and jaspers). If the chunk of mineral makes it through the cutting, grinding, and finishing process, it will last on the knife. I thoroughly test the stone before using it on a knife handle. I've seen some beautiful rock that I can't use because it's too friable. Stone is tough. I had one knife client return a knife to me for sharpening and reconditioning after years of use and abuse. The blade was scratched and beaten, but the gemstone handle looked like the first day it left the shop... amazing. Just ask yourself what are the longest lasting tools, implements, art and artifacts created by man made of? Why, stone of course.

Stone is beautiful. Nothing can match Gods' geologic creations from our planet for color, pattern, and texture. One of my complaints about gemstone in jewelry is that you can only see a small piece of stone, not getting a real feel for the full pattern and characteristics, and you can't hold it. Gripping a dense chunk of polished gemstone and steel in your hand is a great feeling. When you pick it up, it's cool and solid. After you put it down and pick it up again, it's still warm from your hand. All gemstone handles are unique, I couldn't make two of them the same even if I tried. Natural rock is distinctive even when scales are cut from the same stone. The feeling is comfortable, the color exciting, the finish striking.

Though you don't see them much in the modern knife world, gemstone knife handles are nothing new. The ancient Persians and Chinese made some beautiful jade handles that would rival work done today. The reasons most modern knife makers do not make gemstone handled knives is that lapidary is a separate, distinctive tradecraft and art, and requires training, investment, and professional skill as well as many rather expensive specialized tools and techniques. Even more than that, good lapidary requires immense patience, as gemstone is much more difficult and time consuming to work, shape, and finish than even a hardened knife blade.

The methods I use to attach gemstones to the handle substrate are both mechanically and adhesively secure, and in the thousands of knives I've made, I've never had one standard mounted gemstone handle fail. Read more about that here.

There are a few other Knifemakers who work with stone handles, and there is some poor work out there. Guys try to finish the stone without lapidary tools or knowledge and burn and pit the finish. They misidentify inexpensive common stone as valuable, such as telling a client that a piece of serpentine is jade (I've seen this a lot). They might finish a piece without rounding and finishing and attaching the handle properly, that is, with cohesive methods of jewelry bonding. I've even seen plastic rock identified as real gemstone, and plastic amber called "reconstructed" because it has 10% "real amber dust" in the acrylic! Real stone has millions of combinations of play and color and light. It has imperfect lines, seams, and occasionally inclusions of other material. You know it when you feel it, it's cool to the touch (or warm if it's been under lights or in sunshine). To find out if it's real, you can tap it with a piece of steel and it "clicks;" a piece of plastic will "thud." The ultimate test is heating up a needle to dull red, then touching the handle. Plastic will melt and smell, stone will laugh at your feeble attempt to burn it.

Learn more about gemstone use on my custom knife handles on my "Gemstone Knife Handles" page here. It will link you to over 630 pictures of finished gemstone handles.

Learn more about knife handles in general on the Knife Handles, Bolsters, and Guards page here.

Return to Topics

I use literally hundreds of types of rock, mineral, and gemstone in my knives. I try to keep them organized, but sometimes it's overwhelming. For example, If I'm making a knife on the fly for inventory, I might stand staring at the racks for an hour, looking, perusing, thinking just what gemstone might look good on the knife.

Most gemstones are known by their common name, not their mineralogical name. Common names vary from place to place, and from industry to industry. Jewelers, construction trades, sculptors, carvers, and even gravestone carvers all have their own distinctive names for particular rock, gem, and mineral.

This photo was highly solarized with contrast enhancement. the labels are actually white.

Short answer: I make those, too.

Long answer: Horn, bone and ivory can be described together. They are porous, so require some care to prevent moisture absorption and drying. Continuous wetting and drying caused merely by changes in the weather will eventually lead to cracking and checking. Don't even think about using them by the ocean! Some of the material can be stabilized or surface sealed, and in ivory this is undesirable. Ivory ages gracefully to yellow and check, which can be beautiful. By the way, I don't use any elephant ivory on any knife handle, in 2016, that became illegal in the United States, so I'm talking about other ivories: wart hog tusk, hippopotamus tusk, mammoth or mastodon ivory, and ancient walrus ivory. There is also a difference in the coefficient of thermal expansion between steel and horn, bone, and ivory, so this will eventually take its toll. Keep them in a stable environment, and out of hot, dry light. Beware of these characteristics, and your knife should age gracefully.

Mastodon, mammoth or "fossil" walrus ivory are a bit more stable due to infiltration of minerals while buried. The "fossil" term is used loosely in knife making, these are not true fossils, because they are not fossilized, that is, replaced over millions of years by stone. A real fossil is a rock, with all the characteristics of a rock. When modern knifemakers use the term "fossil walrus tusk" or "fossil ivory," they are referring to ivory that has been buried in the ground for thousands or tens of thousands of years and has absorbed some of the mineral stain and is lightly impregnated with minerals that change the color and hue of the original ivory. This hardens it somewhat, but it is still ivory. The correct term would be "mineralized," or "ancient." I also used petrified ivory tusk, which is solid rock. Read more about horn, bone, and ivory on a dedicated page here.

Hardwoods can be magnificent on knives, and are the choice of many owners and makers, and I use them too. They are tough, resilient, and some are very hard. But they, too, can absorb moisture, liquids, corrosives, and have a different expansion coefficient than steel, which may lead to changes over time, and if severe, loosening of the handle. So it's good to opt for stabilized hardwoods, or sealed hardwoods, or extra oily and resinous hardwoods like cocobolo, rosewoods, ironwoods, and lignum vitae. Hardwoods are comfortable to hold and most of them are light in weight, helping balance a knife. They need to be attached with pins: for mechanical as well as adhesive fixture. They can be scratched, dented and dinged, and some darken with age and exposure, but most of this change is moderated if the knifemaker practices good application and sealing and finishing techniques, and the user routinely cares for them (see "Care of your Custom Knife" here). Learn more than you ever wanted to know about hardwoods and stabilized woods used in modern custom knife handles on my "Custom Knife Handles: Woods" page here.

I use plastics also, but usually only on request, and I never use "plastic rock." Most of the manmade (plastic) material I use is Micarta®. It is tough, hard phenolic thermoset plastic originally created as a high strength electrical insulator, and sometimes reinforced with canvas, linen, or paper. This is usually used on military knives and it is bead blasted or sandblasted for a rough, textured grip. Micarta is impervious to everything but heat, and it is lightweight. But it is not exactly what you could call beautiful. It attaches very well, is strong and long lived. I also use G10, which is an epoxy reinforced with fiberglass. I've also used pure nylon on special projects, pure acrylic, Delrin, vulcanized fiber, carbon fiber, and even Teflon. These can be a good choice for tactical knives. I don't make "soft" grips like Kraton, because it has to be molded onto the knife, and flexibility will eventually lead to durability problems. Not many of my clients ask for that type of handle, either, as it is weak and short-lived. Learn more about these and other manmade handle materials on a dedicated page on this site here.

I use Kydex® for combat and tactical sheaths, which is a blend of acrylic and PVC. Colors available are black, gray, camo desert, camo forest, digi-Polar, digi-Forest, and digi-Desert. I also use the polished form: Concealex® These thermoset materials repel just about anything except high heat, and might become brittle in Antarctica (see "Care of your Custom Military Knife here). Learn more about the manmade sheath materials I use on a special knife sheaths page here.

Return to Topics

The mainstay of the knife maker is the 2" by 72" grinding belt. There are a hundred different types, all manufactured for specific purposes, for certain materials, for dedicated applications. Suppliers give discounts if purchased in volume.

Abrasives are the heart of shaping and finishing, and modern craftsmen owe their success to modern abrasives technology. This is not your Grandfather's sandpaper. I use 15 different grit sizes, six different materials, four different structures, and eight different bonds on five different backings of belts from six different manufacturers.

The colors of the belts actually mean... nothing!

Short answer: You'll be handing it down to your grandson.

Long answer: The first word that describes modern handmade and custom knives is durable. My handmade custom knives are fine, well-made instruments and tools. The fit and finish are excellent, so corrosion won't start. The materials are impervious to just about anything you can throw at them. The woods are either decay-resistant or pressure stabilized and sealed. Gemstones are hard, tough, may be sealed, and are impervious to all fluids. Most of the steels are stainless, the guards and bolsters are corrosion resistant or corrosion proof, and attached with at least two zero-tolerance peened pins. Guards are closely fitted and dissimilar metals are soldered. Pommels are tapped, threaded, and every piece is assembled with jewelers quality water-clear epoxy. Most of the knives should last 3 generations or more with reasonable care. It is interesting to note that if you have one of my knives that has a stainless steel mirror polished blade, with 304 stainless bolsters/fittings and a gemstone handle, the most ambitious care requires only an occasional dusting and waxing. Most gemstones will outlast the blades.

It gives me great (if somewhat apprehensive) satisfaction that ninety percent of the pieces I make will still be admired centuries after my bones are dust! They will, however, continue to appreciate in value. Unfortunately, I won't be able to benefit from that-

Return to Topics

A large variety of cutting tools are used to cut other tool steels. This is a chamfer bit, used to dress the angle on the secondary cut for knife handle finger holes. Aggressive tool steel bits like this are specially made, this one is in M2 tool steel, a steel I've used on knives before. But it's an ugly steel and does not finish well.

Steels used to cut other tool steels must be used with great care, with attention to speed feeds, pressures, and lubricants. Of course, all of this cutting must happen before the knife is hardened and tempered.

The photo was taken with outside backlighting, adjusted for color balance and contrast under tungsten lighting.

Short answer: That's impossible.

Long answer: There is no such thing as perfect. Though the human hand can be very well practiced, it is not possible for it to create any object of perfection. Show me any knife, any sculpture, any work of art and I can find irregularities, mistakes, an errors, or a flaw. Anything.

Sometimes people think that if an object is constructed entirely by machine, it can be made perfectly, without flaw. This is, sadly, one of the most persistent and mistaken beliefs that permeate our culture. Items and objects created by machine are limited by the process and that is the first imperfection. What that means is that a Computer Numerically Controlled (CNC)device can only cut what can be held, measured, indexed, and manipulated by the machine itself. The machine limits what can be produced by its own nature. Add to that the human input that has programmed it, the human hand that chooses cutters, initializes, and designs the operation, and the imperfect hand is afoot. No machines are capable of fine finishing to the degree of hand finishing, and cutters, variations in wear, machine play, lubricants, and the materials themselves are all imperfect in make-up and execution.

So if a machine can not make a perfect item, can the human? Absolutely not. Everything is variable by degrees. Here's a great example: I was at a fine custom knife show, and an artist who was touted as one best engravers who ever lived had some items on display. I wanted to see what the items looked like close up, and I had seen many of his representative works in magazines and periodicals. Upon arriving at his table I put on my glasses. If you're over 45, you know that magnifying glasses become a necessity. As we age, the pupils stiffen, and you simply can't focus on nearer items. The glasses I had were only 1.25 magnification, so it wasn't like I was peering through a microscope, which is what he used to engrave the knives. These are glasses that would allow one to read the text on a newspaper at 24 inches. What I saw was a significant variation from what I had heard about this guy's work, and what I had seen in the small printed photographs. There were a few overcuts, some misaligned shading, some places where curves and cuts were not the best executed. What this told me was that the idea of being one of the best did not have to do with perfection, it was his overall designs, knife skills, reputation, and longevity that made him popular. Simply put, his work was imperfect. His knives sold for many thousands of dollars, imperfect every one.

Please remember that typically, the magnification factor of most knives presented on the internet, in websites, and in print media is actually negative. Put another way, what you are looking at is a reduced size, an image smaller than the knife actually is. This is well-known in photography as a technique that will hide flaws, imperfections, and irregularities. If a photo is half the size of the original item, the flaw is also half the size. If a 12 inch long knife is actually presented in a photo that depicts the knife as three inches long, it is a four power reduction. This is a tiny rendition of the knife, and flaws may be invisible. It is no wonder why this size photo dominates nearly all products on the internet, a place where the size of the photo is not critical anymore, since most of the world is not limited by bandwidth and display speed in photos anymore.

This is why I include an array of photos on my individual knife pages, including many that are significant enlargements of the knife, bolsters, fittings, handles, and sheaths. Few people do this because they don't want you to see any flaws or irregularities in their work. I know that these exist, but in an effort to be clear, show them anyway! I want my clients, patrons, and knife enthusiasts to see the knife, the real, handmade knife.

It does not take an expert to detect imperfection. Anyone given enough time can find something amiss or unsuitable with any item, no matter how it is created. In some cultures, it is expected that an obvious and even dominant flaw, mistake, or error is placed in the object so the viewer knows the frailty of the human hand that produced it. There can be a lot of respect for our imperfect nature; it's all part of being human.

A person who demands absolute perfection is not only unreasonable, but also may suffer form a form of obsessive-compulsive disorder. As an artist and maker of fine knives and sculpture, it will be impossible to satisfy this person. Though I make a knife as well as I possibly can, and you can see the results of that in the thousands of photographs on this web site, there is not a one that is, or ever will be perfect. And every one of them can still be unique, useful, durable, valuable, and beautiful in their own right.

Do I worry that my knives are not perfect? No. I've been making knives for so long that I'm very, very good at it. As one of those imperfect humans, I'll continue to strive for perfection, and until then, I'll just make excellent knives!

Return to Topics

I don't get enough time behind the stick. That's a welding term if you're wondering. It takes some fairly advanced tools and techniques to weld some of the exotic and unusual materials I use in the fine handmade knife trade. Martensitic stainless steels, titanium, aluminum alloys and bronze, copper, and nickel silver can only be welded in the GTAW (Gas Tungsten Arc Welding) process. Here the weld is up close and personal, I'm welding a bronze casting for a sword guard. I'm inches away and using a 3 power magnifier under my auto-darkening space aged hood. When I started welding in the mid-70s, this type of weld was not even possible in the small shop. Tools have advanced considerably.

The photo was taken in ambient light, with a star pattern displacement filter applied.

Short answer: It's custom. You decide.

Long answer: Sometimes, this is the hardest question to answer, and often the first question a client may ask. You might think that a client ordering from a custom knife maker would know exactly what he wants, but because there are so many options available, it may be overwhelming to clarify his exact needs for each particular knife.

The easiest way to decide is to determine how the knife will be used, or even whether it will be used. The heaviest use knives I make are military combat knives, and the lightest duty knives are the sculptural art pieces or collectors knives. This doesn't mean that a knife built for collecting is not or can not be used, because those knives are built to the same tough standards as the combat knives. The main difference is that working knives are made to be worked with, used, scratched, abraded, scuffed, sharpened, and often encounter dirt, debris, moisture, and other detrimental exposures. Collectors grade knives are meant to be mostly stored, displayed, and are expected to retain and even appreciate in value. Between these two extremes are most knives, knives that are occasionally used, periodically stored, and expected to retain some if not all of their original value, and even sometimes appreciating in value. So to initially decide, you must consider several factors: frequency of use, intended long term value, and initial cost. The most important thing to decide is which of these types of use your knife will see: serious use, occasional use, or collector’s grade?

Blades for combat, tactical knives after heat treat, and ready for 360 grit, or 40 micron grinding stage.

Blades are sprayed with layout dye for indication of grinding. There is no shortcut to blade grinding to mirror finish, each step must completely remove all scratches (cuts) from the previous step. This is a long, tedious process and I believe that is why you don't see many well-made mirror finished steel knife blades.

The "220" on the blades reminds me of the last grinding step. The eye can't tell the difference in grit scratches, particularly in the finer grits.

Color, spray shadows, and dynamic angle all suggest progress in this photo.

Short answer: It's a knife. Of course it's sharp. Be careful.

Long answer: All knives have cutting edges. But so does an ax, a hand plane, and a chain saw. Even factory knives have edges. What's the difference? The difference is in blade geometry, an often neglected factor of knife making. In order for knives to be sharp, they must be thin where the edge is relieved and maintained (that's the cutting edge). So pay attention to the thickness right behind the cutting edge. The blade should be strong enough to take some use, but not abuse; it's a knife, after all, not an axe. The key to good thin hollow-ground blade geometry lies in the skill and practice of the knifemaker. Factories grind with CNC machines, or with jigs, or with little kids in Pakistan, so they leave the blade thick. This makes for a tough-looking knife, but after three sharpenings, it's so thick that it now has a "chisel" edge, unsuitable for cutting. Factories think that this is when you'll just go buy another knife. A properly hollow-ground knife blade is thin throughout most of the blade, so that repeated sharpenings will still leave a usable, thin geometry. Another factor of good blade geometry is in the method of grinding. If the maker uses a jig, or has bad technique, he grinds straight across the blade, neglecting the curvature or belly of the blade shape. This leads to thick and thin areas of the blade: not good. Particularly noticeable with this method is a very thick point, exactly what you don't need in a knife! Why have a point if it's not thin and sharp? A skilled knifemaker grinding offhand follows the curvature of the blade with the hollow-grind perpendicular to the edge along the entire edge, leading to uniform thinness throughout the cutting edge. This makes devastatingly sharp bellies for skinning, dressing, or tactical knives. It also makes thin, aggressive, extremely sharp points. Take a good look at that bulky factory steel. Isn't it just a bar of metal that's dressed up to look like a knife? See detailed drawings about cutting edges, blade geometry, relief angles, and custom knife blades on my Blades page here.

Return to Topics

There are countless measuring tools and reference guides in the modern machine shop. Measurements have to start from a fixed, verifiable, absolute point of reference. In this case, it's the granite base this height gauge is resting on. The granite is lapped and polished to extremely high accuracy, about 1/10,000th of an inch in variation.

This gauge is actually an antique, with handmade parts. It's heavy, solid and well made. It's used to transfer a set height to various objects via a hardened, pointed scribe.

In the photo, I went for very narrow depth of field to accentuate the point, and applied a light wash in the axis direction of the main rod.

Short answer: Not if you take care of it.

Long answer: Different steels are different, but there is no "rust-proof" tool steel. The addition of carbon to iron (to make steel) means that it can corrode. Steels that are "rust-proof" do not classify as tool steels (like the 420 stainless used in knives sold in late night infomercials), and they can be used as knife blades, but they are weak and short lived. Sure, you might see one of them cut a soft tile then a tomato, but their ability lies in the thin edge, which quickly wears away. They are very tough (that's flexible, with resistance to breaking), but so is a spring. In fact, that is almost exactly what they are: soft, thin stainless steel springs. You wouldn't take one on your favorite deer hunt, or into the combat theater, or hand it down to your grandson. Other corrosion-proof knives are dive knives. These are often made of 316 stainless steel, which is used in making stainless pipes to carry chemical corrosives, such as acid. Others are made of titanium which cannot be hardened any more than 35 Rockwell on the C scale, whereas knives are typically 58C Rockwell, dozens of times harder and wear resistant. These blades won't corrode, but are also soft and weak and do not classify as tool steel.

Corrosion can occur on fine stainless tool steel knives, but only if you let it. A high quality 440C stainless knife steel will only corrode if left exposed to sea water (for a long time, longer than a day or two) or orange soda pop, or battery acid, or left in a wet leather sheath (acids are used in tanning leather) or stored long term in the sheath and not allowed to breathe, unwaxed and unprotected. ATS-34 is a bit less corrosion resistant, so blood, orange juice, etc. will also stain it. D-2 is even less corrosion resistant, and I've seen people's acidic fingerprints etch into the blade finish. And O-1 will flat out rust, unless you keep it coated with car wax, or Break-Free®, or silicone-based polish-sealants. A high mirror polish on knives can help, as debris cannot cling to the blade. There are some new developments in the nitrogen stainless steels that have extremely high corrosion resistance, but these steels are very expensive, limited in production runs and sizes, and typically only used for dive knives in marine environments

So what to do? Clean your knife, keep it reasonably dry, wax it periodically, do not store it long term in the sheath, and it will be just fine. Read more about knife care on a dedicated page here.

Return to Topics

The buffers are the most dangerous machines in the shop. They spin cloth, felt, or other material at a very high rate of speed, in the order of over 110 miles per hour at the surface. They can catch on any projection of the item being polished, and the item grabbed, spun, and thrown back at the operator before his heart can beat one time.

I've known of several knife makers killed by these machines, but nothing can match a well polished metallic surface.

Photo constructed for high depth of field, dynamic angle.

Short answer: They're dark.

Long answer: Several clients have asked why active duty military would carry mirror finished blades into combat where they lack "stealth." I explain that some of them are spraying the knives with camo paint, sheaths and all, then washing it off with denatured alcohol when they return from their deployment. This way they've protected the finish somewhat, and had something very nice to place on their mantle afterwards, eventually to hand down to their children. Others leave the blades polished, and figure if they have to pull their knife, the situation has already gone to hell and some shiny high-chromium tool steel might make an influential.... statement.

Coatings: I do not typically coat blades, because that would hide the grinds, hide any potential flaws, eventually chip and peel, and may actually accelerate corrosion. I go into detail about this topic including a section on Parkerizing on my Blades page at this bookmark.

Bluing is a process of oxidizing (rust is a form of oxidation, uncontrolled and irregular). Hot bluing (which is what I do) is a controlled, deep passive oxidation process whereby the steel is cleaned thoroughly, chemically and molecularly, then immersed in a superheated boiling solution of sodium nitrate and other salts for 40 minutes or longer. This deeply oxidizes the surface of the steel. The bluing process is the same used on all fine firearms, that black, dark look that takes years to buff, scrape, or polish off. My process excels in penetration, where most firearms might be blued for 10-20 minutes, I start at 40. To give you an illustration, when I cut my makers mark into a blued blade using a sharp stylus diamond point engraver at 50 pounds per square inch, it takes three full passes to cut through the bluing to achieve a bright cut.

To sum, hot caustic bluing is a well-recognized, time-proven method of inhibiting corrosion (not preventing it) on the surface of steels. My own son (in the US Army 101st Airborne) has carried a hot-blued skeletonized knife in combat in Iraq. So has his squad. They're very happy with the performance.

Please remember, there is NO corrosion proof tool steel. Even 440C, which contains 18% chromium will rust and corrode in salts or acidic environments. There are some new developments in the nitrogen stainless steels that have extremely high corrosion resistance, but these steels are very expensive, limited in production runs and sizes, and typically only used for dive knives in marine environments.

Please look at my "Care of Your Custom Military Knife" page on this website and the "Will it Rust?" topic above.

Return to Topics

The wet grinding bench and related apparatus is for gemstone. The body of the grinder is stainless steel, all fittings, shaft, and mechanical parts are stainless steel because it is constantly under water. In my early years, I would heat the water sump to boiling to keep my hands from freezing and cramping, particularly in the winter while grinding rock. The heavy neoprene gloves help some, but have to be removed when fine finishing takes place under water.

Nearby equipment must be protected from water spray.

Photo is from bench level view, gloves on petrified dinosaur bone and flint dressing stone.

New! While I'm not hot-bluing stainless steel blades, I've developed a new process for stainless steel counterterrorism knives in my "Shadow" line that creates a subdued, dark, and variable finish for non-reflectivity!

Short answer: Can be done, but why?

Long answer: There are several methods for bluing stainless steel. They are complicated and expensive, compared to the standard process of bluing carbon steels (see "What about blued blades and coatings" above). First, please consider why stainless steel is "stainless" in the first place. It's because of chromium, and we're all familiar with the permanence of a chrome plated bumper of a car (though newer cars are plastic, yecch!). Chromium steels are resistant to corrosion because they form a passive oxide coating at the surface as soon as it's exposed to the atmosphere. Aluminum has a similar property. So corrosion (rust) does not easily start. The most common reason to blue a blade is to impart a corrosion resisting controlled oxidation to the surface of the steel, that way it inhibits further corrosion. Since true stainless steels contain a lot of chromium (more than 13% to be classified as stainless), they are already more resistant to corrosion than a blued steel. So the only reason then to blue a stainless steel blade is for color and appearance.

Though stainless tool steels can be blued, currently, I do not have enough requests to add an additional and expensive bluing bath for stainless steels to my already huge list of processes. I get requests for blued stainless about six times a year, and that is not enough to offset the cost of the chemistry, tanks, and process, a cost that ultimately, I would have to pass on to the clients. Also, from what I've determined by study, the blued stainless tool steels have a questionable and variable appearance. Perhaps in the future it will be worthwhile to blue stainless tool steel blades. Right now, it's not just cost effective, and no advantage for corrosion resistance is obtained.

I go into detail about this topic including a section on Parkerizing on my Blades page at this bookmark.

Return to Topics

Folding knives require tough, rigid templates to lay out the patterns and align the holes to be drilled or milled into the final knife liners, blades, bolsters and components. So, in addition to the plastic patterns that represent the finished knife profile, I have a group of metallic templates racked and labeled for the folding knives.

Patterns for knives may be passed around among knife makers, or even given to other makers after a death. Even with the pattern in hand, each maker applies his unique style, arrangement, materials, and finish to a knife pattern, and thus, puts his own name into the work.

Photo is high contrast, embossed manipulation.

Short answer: No. Read, study, ask, learn, and make the best purchase you can afford for your intended use.